MAPS: A WRITER’S RESOURCE

by

Michael A. Petry

A critical thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of

Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing for Children & Young Adults

St. Paul, Minnesota

December 2013

Faculty Advisor:

A well-written novel engages readers and draws them into the story, or as John Gardner writes in The Art of Fiction, draws us into the characters’ world as if we were born to it. “By definition – and of aesthetic necessity – a story contains profluence,” (53) “our sense, as we read, that we’re ‘getting somewhere.’” (48)

To do this, “the writer must do more than simply make up characters and then somehow explain and authenticate them… He must shape simultaneously… his characters, plot and setting, each inextricably connected to the others; he must make his whole world in a single, coherent gesture…or as Coleridge puts it, he must copy, with his finite mind, the process of the infinite ‘I AM.’” (46)

Gardner goes on to write that plotting “must be the first and foremost concern of the writer,” (56) and that “when designing a profluent plot…the writer works in one of three ways, sometimes two or more at once: He borrows some traditional story or action drawn from life; he works backward from his climax; or he works forward from an initial situation.” (165)

I would argue that another useful tool in designing a profluent plot is a map. Maps can facilitate the writing process by assisting the writer in creating the setting through scale and location, developing character, and moving the plot forward.

The word “map” comes from the Medieval Latin Mappa mundi, where mappa meant napkin or cloth and mundi the world. Thus, “map” became the shortened term referring to a two-dimensional depiction of the surface of the world.

A map is a visual representation of an area – a symbolic interpretation that highlights relationships between elements of that space such as objects, regions, and themes. Some maps are fixed two-dimensional, geometrically precise representations of a three-dimensional space like those we often use when navigating on a road trip; others can be interactive like that in a GPS system.

Maps are the primary tools by which spatial relationships are visualized. Maps therefore become important documents.

“A map does not just chart, it unlocks and formulates meaning; it forms bridges between here and there, between disparate ideas that we did not know were previously connected.” – Reif Larsen, The Selected Works of T.S. Spivit

Although most commonly used to depict geography, maps may represent any space, real or imagined, oftentimes disregarding scale. Writer and artist Austin Kleon wrote that although maps are often used for sci-fi and fantasy “every tale has a setting, every tale creates a world in the reader’s mind,” and that drawing that world can lead to better fiction.

Phillip and Juliana Muehrcke wrote that, “the essence of maps … is probably best characterized as controlled abstraction,” and that many writers demonstrate ways that, “the abstract nature of maps stimulates fantasy and imagination, leads to frustration, fosters speculation, aids (and sometimes hinders) decision making or facilitates understanding.” They go on to say that, “the very fact that a map does not reproduce reality is its great allure.”

Maps and Plot

The plot of a story starts off somewhere with a character and the setting that surrounds that character. I like to think of maps as these three elements combined. Many stories have physical journeys that take them from one location on a map to the other. Here is where a map can be of tremendous power to a writer’s story.

The characters we as writers have in our heads want to move around, they will experience their environment whether they are traveling through the forest, across a desert, or leaning over the edge of a ship puking. How do they experience a narrow ledge while traveling over a mountain pass? Maps that a writer creates can help make clear the setting in which our characters interact, struggle with, and overcome.

In Tolkien’s The Lord of the Ring Part I: The Fellowship of the Ring, Frodo makes what I consider to be one of the best quotes about journeys that we as writers do with maps and our characters. Frodo is speaking to Sam and Pippen about what Bilbo told him before he left:

“’He used to often say there was only one Road; that it was like a great river; its springs were at every doorstep, and every path was its tributary. ‘It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door,’ he used to say. ‘You step into the Road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there is no knowing where you might be swept off to. Do you realize that this is the very path that goes through Mirkwood, and that if you let it, it might take you to the Lonely Mountain or even further and to worse places?’”

How cool is that? It makes me want to draw up a map right now just to see where it could take a new character that I haven’t met yet. “Maps are essential. Planning a journey without a map is like building a house without drawings,” writes Mark Jenkins in The Hard Way: Stories of Danger, Survival, and the Soul of Adventure.

Plot has various steps like the beginning, a rising action, the problem or conflict, a climax or the darkest moment, the falling action or the results of the characters choices, and the resolution. How does a map help with these elements of plot?

Personally I like to know where on a map, when one is provided, the story begins. Are we on the outskirts of a small village or up in the mountains hunting to provide food for an uncle, only to miss the deer he’d been stalking all day, then to miss when a bang and a flash appear only feet away from this new character, as in Christopher Paolini’s Eragon?

We know that in The Hobbit Bilbo and his dwarf friends, Thorin and Company, start off at Bag End in Hobbiton and that their journey ends at the Lonely Mountain. There are major stopping points that Thorin and Company travel through after they leave Hobbiton, with changing scenery as their journey progresses. As writers we get to see this open up as we write. Our writing journey is much like that of Thorin and Company; we start out with a story idea and outcome and go after it. Maps give us some insight as to things that may or may not happen along the way. Like any adventure, if we prepare by plotting ahead I believe that we subconsciously figure out what to do when the story line gets problematic and the proverbial plot thickens.

Maps don’t have to be so specific that they show us exactly where the characters are at all times, but to know where the village is in relationship to the mountain range that the main character is hunting gives us a great beginning. Maps are there to guide us to unknown stories yet to be discovered if we can just get a plot, an interesting character, and setting to bring to life the places that they are in.

The next element in plot is a rising action. This often takes place on the map where the story begins or close to it, but we will get more details about the plot and what is about to happen. The setting up of a map either before your story begins or as a process as the story unfolds can aid and move the plot forward. A map is not there to take front and center, it’s more of a supporting character that gives us as writers a nudge and says hey, maybe we could take this plot over to the coast or to some high snowy mountains or into the desert developing conflict and opportunities for growth.

The problem or conflict part of plot to me is where the journey really begins. This is what led Frodo and Sam in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of The Rings The Two Towers to the Dead Marshes with Gollum as their guide. This relatively simple part in the Middle Earth map that says Dead Marshes screams to be explored and traveled through. What conflicts will the plot experience as the story moves across the map?

As writers and map makers will we know on the map where the climax of the story is? Did Tolkien know that it would be at Mt. Doom? Did he know the path before the story began? I believe that maps are powerful enough tools to tell us where the darkest moment of the story will be and rich enough to give us the plot and setting that the main character must react to.

Maps may not be as important in the last two elements of plot with the result of the falling action and the resolution, but the map helped get the plot there.

Here is the map that Thorin’s father left to Gandalf. This map shows in greater detail The Lonely Mountain and surrounding areas. Also the map is oriented with east pointing up.

When Bilbo and the hobbits leave Rivendell they head into the Misty Mountains. Tolkien describes in chapter four of The Hobbit how Bilbo and the dwarves encounter the dangerous crooked pathways that you find in mountain passes, with rocks falling and chilly nights with no comfort, and loud echoes that sounded uncannily as though the silence disliked being broken. The wind wailed and the stone cracked. The effect of the setting here made the group solemn with gloomy thoughts.

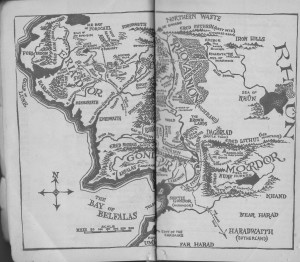

The entire journey from the map of Middle Earth shows us roads and rivers, coastlines and mountain ranges. We also see great expanses of forest, cities, and places of import that Tolkien saw fit to add to his maps. As Thorin and Company move through Middle Earth on their quest the map aids the reader in outlining the locations and setting. We know that they escape down the river to Long Lake, then to Lake Town, then the town ruined by Smaug, the dragon, to see the Desolation of Smaug, a land that the dragon destroyed and defiled. Thorin and Company finally reach their destination of The Lonely Mountain, their ancient home. Each new location along this path has a unique environment and setting.

Journeys like those in Christopher Paolini’s Eragon series that take us from one place to the next through various landscapes and across the maps of their world give us as writers a good example as to how we can explore new setting as characters arrive there. The landscape of Alagaësia starts off in Eragon’s home village of Carvahall in Palancar Valley. A curious question that has cropped up while reading and researching the topic of maps in novels is when did the map become necessary?

In just looking at the map at the front of Paolini’s first book Eragon and studying it, then looking at the content pages of each chapter title, we know that Eragon takes his journey from Carvahall to Therinsford, then to Yazuac, through Daret and out to the coast to Teirm. Eragon, Brom, and the dragon Saphira head back over the mountain pass through The Spine to Dras-Leona back north skirting the capitol of Urû’baen to Gil’ead then across the great expanse called the Hadarac Desert . In this the first book that Paolini writes he takes his key characters eventually to Farthen-Dûr in the Beor Mountains where the dwarves live.

As writers we can visually see just from the map that they start off in a remote northern village set amongst the northern mountains called The Spine. Depending on the time of year there could be snow or maybe there is snow year round in these parts. As Eragon, Saphira, and Brom head south they encounter places that neither Eragon nor Saphira, who is only a few months old and being trained by Brom on their journey, will experience, such as when they leave Therinsford and descend out of the mountain outlook of Utgard towards Yazuac. Paolini describes the slow steep descent out of The Spine where there were loose rock making their footing treacherous. When they reach the bottom and the beginning of the plains Eragon is unnerved by how flat everything is and how the wind scours and whips unmercifully.

This summer at Hamline University’s July MFAC residency Ron Koertge spoke on creating a map to move the plot of the storyline forward. Sometimes in writing we need to create maps so we know how our characters will integrate with the landscape. His story was taking place in a real world setting and he found himself stuck and not able to continue his story. He sat down and started to draw the few blocks where his story, Stoner and Spaz, was located and by so doing was able to visualize where his story needed to go and was able to complete his book.

This summer at Hamline University’s July MFAC residency Ron Koertge spoke on creating a map to move the plot of the storyline forward. Sometimes in writing we need to create maps so we know how our characters will integrate with the landscape. His story was taking place in a real world setting and he found himself stuck and not able to continue his story. He sat down and started to draw the few blocks where his story, Stoner and Spaz, was located and by so doing was able to visualize where his story needed to go and was able to complete his book.

Maps and Character

Character is made up of who the person is, their back story, their conflict, and desires they have. Maps help develop character in that they offer what is most critical to a character. Maps aid and facilitate how characters react to the elements of plot and how they react to the elements of setting. A fantasy map gives a writer a place to drop a character into a new world. Where will the character start and end up and what will that character experience in the middle?

How can a map help when thinking about a character’s back story? I am constantly looking at maps to know where my characters have been. I’ve visited some of the places that my characters will be and experience. However, if your story doesn’t take place here in this world then you have to create a map, and your back-story map might be different than your current map. It might be somewhere far away across a vast ocean. It could be the same map but just a different time. Did the character live in a time when technology was advanced but something happened and civilization dropped into a dark age? Maps can support the past history of the character and give writers a place to start. Mapping isn’t just drawing up continents but could be mapping a character’s family tree and where he or she came from.

Mapping is much more than just what this critical thesis is about. The conflicts that shape our characters can be shown on the maps we create. When asked to draw up a map of my current creative work I didn’t really need to draw up a map, at least I didn’t think so. I had been struggling with really knowing who my character was; I didn’t know what made him tick or what belief and desire he had. I had an idea but nothing clear. So I drew up a timeline map with the locations and settings as a sideline. My timeline delved into my character’s past, before he moved to where the story takes place, and some key locations of major events that I hadn’t known about him until I was asked to undertake this process.

Maps can also help foster relationships with characters. This can be done by defining regions or trade routes or countries whether friendly with each other or at war.

In George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series in the world  and land of Westeros he has come up with regional names for bastard children. In the north it is Snow, for the Iron Islands it is Pyke, for the Riverlands it is Rivers, for the Westerlands it is Hills, for the Reach it is Flowers, for the Stormlands it is Storm, for Dorne it is Sand, and for Dragonstone and King’s Landing it is Waters.

and land of Westeros he has come up with regional names for bastard children. In the north it is Snow, for the Iron Islands it is Pyke, for the Riverlands it is Rivers, for the Westerlands it is Hills, for the Reach it is Flowers, for the Stormlands it is Storm, for Dorne it is Sand, and for Dragonstone and King’s Landing it is Waters.

Each bastard child’s surname is defined by where they live. How does the burden of growing up with the surname Snow affect the character development of Martin’s character John Snow? John grew up as Lord Eddard (Ned) Stark’s bastard child. No one except Martin really knows who John Snow’s mother was except that Ned Stark wouldn’t speak of her and that he cared for her enough to not speak ill of her, even to his good friend the King of Westeros, Robert Baratheon. Though Ned loved his bastard son, John Snow would never have claim to his father’s house. When Robert Baratheon visited the Stark home in the north John Snow did not sit with his half brothers and sisters. This is a great example of the power and usefulness of maps in aiding rich character development and creating conflict. It is the conflict, after all, that drives the character to act and do the extraordinary.

Maps and Setting

Setting is more than just a backdrop for the action of a story; it is an interactive aspect of the fictional or real world. Setting includes but is not limited to scale, location, climate, time, built environment, and human scale.

Scale

Scale can be identified in the environment that surrounds the character as the size of a city, the distance from one side of a city to the other, or how long it takes to travel from one city to the next. Novels also use differing modes of transportation that can give the writer a sense of scale and distance, such as by boat down a river or on the open sea, by wagon, by horse, by dragon back or by worm back. As writers we can choose to use different means to scale lengths such as measurements in leagues, miles or meters.

In novels, scale is the relationship between the character and their surroundings that locate them as they move around in their world. The initial setting found within the first few paragraphs of a story gives us that scale and location.

This opening scene is usually tight and close to the main character. In Kazu Kibuishi’s Amulet: Book One The Stone Keeper, Emily is in the car with her mother and father late at night on a narrow curvy road going to pick up her brother Navin. As writers we know where the characters are and the scale of the place. We know the scale because we know how we fit into a car. Scale is just that, the sense of knowing the size of something in relationship to ourselves in our environment. The location is a by-product of the character’s relationship with their environment.

At the end of book one of the Amulet series Emily, her brother, and some new friends need to reach the nearest city of Kanalis in the land of Alledia to find an antidote for Emily’s mother. Morrie lets us know where they need to go, and Miskit gives us the scale by miles and how long it would take to do on foot.

“Kanalis is the nearest city. We can probably find what we need there.”

“But that’s three hundred miles from here… Without the Albatross that trip may take weeks.”

This aspect of scale is a time and distance comparison. Another aspect of scale is the comparison of human scale and how that relates to zooming in or out, like in this example.

Here Cogsley, the grumpy robot chimes in. “Hey, did you clowns already forget? We’ve still got one more vehicle.” The reader is introduced to the mobile walking house. We get a good idea how large the walking house is because of the human scale of Cogsley. He operates the house from his command chair as he looks out to drive. Kibuishi does an excellent job zooming out to give us as the reader the full sense of scale as well as informing himself as the writer.

William Alexander’s Goblin Secrets begins with Rownie being woken up as Graba knocks on the ceiling, knocking plaster down into Rownie’s eyes. He gets up from a bed that is made of straw and covers the entire floor, stolen clothes that have been sewn into blankets and sleeping siblings all around him – boys on one side and girls on the other. They pull the rope that lowers the stairway down from the ceiling of Graba’s loft that is filled with mostly pigeons and some chickens. We get a sense of where we are and the scale of the story in which Rownie’s world is taking shape as he is woken up. The pull-down stairway from the ceiling gives us our first sense of scale of this house, although it is still vague as to just how big or small the house is. We know how large stairs are even if they vary in small ways as to actual measurement. This is scale at the get go of the story that grounds us to the character as much as to their environment.

Scale helps us as writers to get a sense of how intimate or vast the space. Patrick Rothfuss’s King Killer Series has a map at the  beginning of the first of his two published books, The Name of The Wind. His main character, Kvothe, spends a good amount of time in both books at the University across the Omethi River.

beginning of the first of his two published books, The Name of The Wind. His main character, Kvothe, spends a good amount of time in both books at the University across the Omethi River.

The city of Imre is two miles away, and the great stone bridge over the river is over two hundred feet long and wide enough for two wagons to pass by each other. The bridge gives us a great idea to scale and how grand a piece of architecture it is. When Kvothe reaches the crest of the bridge he sees for the first time the University’s Archives rising above the trees, another sense of scale.

Kvothe lives alone in Tarbean from the age of twelve to fifteen. We find out that Tarbean’s population is over 100,000 and that you cannot walk from one side of the city to the other in one day. Scale is an interesting concept; one might think that one hundred thousand isn’t actually that large according to the huge cities around the world today; however, the city of Billings, Montana is the only city that is just over 100,000 in population in a five-state region, so scale in numbers is relative.

Another example is from Frank Herbert’s Dune. The giant Sandworms (Shai-Hulud) of Arrakis grow to be hundreds of meters in length, with specimens observed over four hundred meters long and forty meters in diameter. The sandworms can be ridden for up to half a day and can travel hundreds of miles in that time before becoming exhausted. Scale is all relative, and it comes back to us as humans and how we fit into the spaces around us.

Scale is an abstract word, and only when you have something that is known to compare it with can it truly be understood. As someone who has worked at various engineering firms drafting, I know that scale means everything so that plans and designs can be understood and built correctly. One inch equals ten feet or one inch equals two hundred feet or three hundred miles.

In Eldest, Christopher Paolini’s second book, Eragon, Saphira, and Orik, a dwarf, leave Ellesméra for the city of Aberon. They are travelling from one of the northern most cities to one of the southern most cities found on Paolini’s map that is included in the novel. Eragon and Orik ride on Saphira’s back:

“A long journey… but yes, we made it. We’re lucky that misfortune did not strike upon the road.”

An exact distance of time is not referenced and Paolini does not include a scale bar in his maps. The reader’s best guess is just that. As writers we need to have a good sense of measurement in our map and be true or consistent with it in our story. We have the choice to determine what type of measurements we will use or none at all.

In the second chapter of Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, various units of measurement are used. The first measurement encountered is a surprising one.

“’The ridge upon which the companions stood went down steeply before their feet. Below it twenty fathoms or more, there was a wide and rugged shelf which ended suddenly in the brink of a sheer cliff: the East Wall of Rohan.’”

A fathom is a measurement specifically used for measuring the depth of water, a unit of length equal to six feet or 1.83 meters. (Merriam-Webster Dictionary) Tolkien’s use of this measurement gives both depth and texture to his description. He could have just used feet or meters but chose to use fathoms.

As the three companions continue their chase of Merry and Pippen, Aragorn stretches himself upon the ground to listen to the earth;

“’The rumour of the earth is dim and confused,’ he said. ‘Nothing walks upon it for many miles about us. Faint and far are the feet of our enemies.’”

Here the measurement is the mile. As you can see by Tolkien’s map he has a scale bar in miles on the bottom left. Scale bars help give more tangible meaning to a map such as Tolkien’s Middle Earth. Many of the maps that I have encountered in novels do not have scale bars. I can only guess as to why authors choose not to use them.

Further on in the chapter Tolkien chooses to switch measurement units from the scale bar on his map again. Over and over again in the second chapter we find the use of the league.

“’Now twice twelve leagues they had passed over the plains of Rohan…’”

“’It is still far away,’ said Aragorn. ‘If I remember rightly, these downs run eight leagues or more to the north…’”

“’Nay! The riders are little more than five leagues distant,’ said Legolas.’”

The last use of league gives us not only a total distance in leagues but in what time the three companions did this trek.

But the use of the league can be difficult to get really good accurate measurements because the league has many differing lengths on land and even references to water speed and distance. Patrick Rothfuss gives a great example of how vague the league really is. In his first book he uses both the mile and the league. Kvothe is inquiring as to have far up the Omethi River and by road is the town of Trebon (not found on Rothfuss’s map). Kvothe is speaking with a female innkeeper about the distance. Rothfuss does an excellent job in giving us both a distance and rough time to complete the trip to Trebon.

“’… ‘By river it is forty miles or so. Could take more than two days depending on if you’re on a barge or a billow-boat, and what the weather’s like.’”

“’How far by road?’ I asked.”

“Blacken me if I know,’ she muttered, then called down the bar. ‘Rudd, how far to Trebon by road?’”

“’Three or four days,’ said a weathered man without looking up from his mug.”

“’I asked how far,’ she snapped at him. ‘Is it longer than the riverway?’”

“’Damn sight longer. About twenty-five leagues by road. A hard road too, uphill.’”

Here Kvothe jumps back in letting us know that Rothfuss has figured out what distance he prefers to use in his writing.

“’God’s body, who measured things in leagues these days?’ Depending on where that fellow grew up, a league could be anywhere between two to three and a half miles. My father always claimed that a league wasn’t really a unit of measurement at all, just a way for farmers to attach numbers to their rough guesses.’”

“’Still, it let me know Trebon was somewhere between fifty and eighty miles to the north. It was probably best to assume the worst, at least seventy miles.’”

In my own writing I have contemplated using leagues mostly because it sounds out of the ordinary to our miles. Merriam-Webster dictionary says that a league is “any of various units of distance from about 2.4 to 4.6 statute miles (3.9 to 7.4 kilometers).” I have found the same to be true from what Rothfuss has told us about leagues. They are vague at best.

Location

Maps and location are so similar and closely tied together that when you look at a map and find a place, any place that is its location. As a writer the location is where we are right at that moment in the story. A great part of map making is the cities, towns, and villages that the characters get to explore and that we get to describe as writers. Where is the city located? How large is it? Are the people there during a time of peace and prosperity or during times of war or famine or both?

The location in the story may be too small to see on a map that is, in scale, too large to show the details. The details do not need to show up on the map, since writers will describe them in the story. Specific places like villages, towns, cities, and places of import found on maps have so much potential to blend into the landscape or to defy and make bold statements.

In Paolini’s first book Eragon, Eragon visits four communities that are small enough to be either villages or towns. We gain more and more setting details like empty houses indicating hard times and the lack of children playing in the streets and weeds growing from cracks in people’s abandoned stone-covered yards. When our characters travel through the maps we create, they see and experience new places and scenes that unfold from one place to the next.

Yet another perspective of a new place found in a created world, is the town that exists in Rothfuss’s map within the Stormwal Mountains. Specific places like villages, towns, cities, and places of import found on our maps have so much potential to blend into the landscape, like the village or town of Haert does, or to defy and make bold with massive walls protecting a central castle like in Paolini’s city of Teirm. Setting and the locations found on our maps are waiting to bleed onto the page as our characters move through our landscape.

Maps help guide us by being general in scope but not too defined to be constraining. I asked a fellow student this last summer if he thought it important to draw up a map of the story he was working on. He said, “No.” He told me that he didn’t want to be constrained by a map. When a map is too detailed it takes over the freedom to explore and change your setting. A larger scale and a broader scope offer more latitude to be descriptive in writing. Location as an element of setting found in maps assists the story giving the story texture and depth. For example are they in a desert, rainforest, the mountains, out at sea? In space aboard a spaceship moving from one planet to the next or traveling through the Dead Marshes heading to the Black Gate, as Frodo, Sam, and Golum do in The Lord of the Rings?

Time

When we create a map we determine the places, environments, weather, and time in its three aspects: historic, seasonal and daily time. How is this done? When I drew the map on my concrete floor I knew I wanted to have a coast line. I thought about how we look at our world, which for me growing up in Washington State included the Olympic Mountains just off the coast, then the Cascade Range that runs from Canada to northern California, so I drew a series of mountains just off the coastline. I drew in rivers and lakes, arid places with mesa topped mountains that are ancient and have eroded that way. The more places and settings that I include the more potential for diversity in a potential plot and ways my characters will be able to react to the setting. More setting isn’t better unless you intend to write a long series and even then may not be necessary; however, to explore new setting is to learn and grow as a writer.

Historic time to me tells me what the technology of the story is. The seasonal time lets me know if there are leaves on the ground or grass, flowers, and buds sprouting from the trees; and the daily time is what time of the day is it. Maps and these three times are very different. Historic (or technological time as I like to think about it) will determine many things as to how characters move from one location and its setting to the next. Seasonal time affects the setting that the character and plot are set in, such as the snow and cold of winter, or the wet and muddy terrain found in spring, or the crisp nights that autumn brings.

The first two aspects of time will be set before you jump into the daily time. Is it dark in the west with a hint of light rising in the east? When I create a map with time in mind I’m thinking of the setting and how the historic and seasonal time correlate in terms of how the plot will move forward and what my characters will learn by how they react to the setting/time element. For example, the character’s access to technological gadgetry is dependent on the historical time element and the seasonal time element affects how they use their technology. How would a northern coastal setting with steep cliffs in the winter affect the character in a futuristic novel versus a less-technological age?

Setting, from the maps we as writers create, wants to jump out of our fingers as it makes itself known like going through a door for the first time and seeing all that was previously hidden from us. It can also be like hiking through a mountain trail up and around each bend; we see bits and pieces of the trail, the reveal-conceal concept.

Climate and Weather

After a few days out on the plains, in Paolini’s book Eragon, Saphira is flying overhead of Eragon and Brom when a storm front approaches.

“’It was calm when they reached the storm front. As they entered its shadow, Eragon looked up. The thundercloud had an exotic structure, forming a natural cathedral with a massive arched roof.”’

Even weather systems that are unique to the different settings give us a writers the environment around our characters. Eragon and Brom realize the danger the storm front would bring Saphira. Even a dragon is no match for the power and strength of a storm. She must land. This scene gives a great many details, about the struggle for Saphira to land and safely get her wings tucked away. Eragon was right there as she somersaulted over him, her spines missing Eragon by inches. What a great visual for the writer and reader alike, and it grows from the creation of a map.

Human Scale and Senses

Scale is all relative, and it comes back to us as humans and how we fit into the spaces around us. This is called human scale.

“Man is the measure of all things, of things that are, that they are; and of things that are not, that they are not.” –Protagoras

Characters interact with their environments based on their physical dimensions, capabilities, and limitations – and human physical characteristics are still fairly predictable and measureable. Scale can be created through description of steps, doorways, railings, work surfaces, seating, shelving, walking, and other features that compare to the average person.

Characters also interact with their environment based on their sensory capabilities. We have five senses that we use: sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste. When I was studying Landscape Architecture I learned that with great design the more elements of the human senses you can invoke the more memorable the human experience will be. This is true for writing as well. A Japanese garden is a perfect example. Small stepping stones in pools slow the experience down, giving time for the people to think about where they step by looking at the stepping stones and the water, then their reflection. Slowing down the story with sensory details gives a character a chance for introspection, directly affected by setting.

Built Environment

We can’t forget the built and manmade environments, too. Cities, castles, a roasting bird over a camp fire, dungeons, cobble streets, smoky inns, and these places evoke the five senses with which we feel our way through everyday life.

It is difficult to talk about setting without talking about plot and character; creating a map helps bond these three aspects of craft together.

“To put a city in a book, to put the world on one sheet of paper – maps are the most condensed humanized spaces of all. . . They make the landscape fit indoors, make us masters of sights we can’t see and spaces we can’t cover.”

— Robert Harbison, Eccentric

In conclusion, I believe that maps ground us as writers, give some sense to what lies ahead, and assist in creating that profluent plot that John Gardner calls necessary. Maps give both the writer and also the reader a sense of the setting and guide the development of the character through their interactions with the natural and built environments – both fantastical and real.

We can’t always know if a writer did draw a map and if he or she did, whether the map was drawn before or after the story was complete. We know that J.R.R. Tolkien drew several of the original maps from the Hobbit but then commissioned his son, Christopher, to complete other drawings that were included in later editions of his Lord of the Rings trilogy. William Faulkner created and mapped a county which was the setting of twelve of his books and more than 30 stories. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island was also inspired by a map. It is also purported that J.K. Rowling spent several years mapping out the magical world in which Harry Potter’s adventures took place.

Although not all novels contain or include a map in their final product, a map is still a useful tool, and it seems that many writers use mapping, be it scribbled drawings on a napkin or formal and detailed, to assist them in their writing process. As mentioned previously, Ron Koertge drew a map to facilitate his writing process in Stoner and Spaz.

I also contacted William Alexander, and he told me that he had, in fact, used some rough-drawn maps when writing Goblin Secrets, as seen in these pictures he shared with me.

used some rough-drawn maps when writing Goblin Secrets, as seen in these pictures he shared with me.

And probably one of my favorite discoveries was this picture of Patrick  Rothfuss. In the background on the chalkboard behind him is a map. I recognize it as the university campus, which is a location and part of the setting in his book series.

Rothfuss. In the background on the chalkboard behind him is a map. I recognize it as the university campus, which is a location and part of the setting in his book series.

I have considered myself to be somewhat of an expert on maps. I grew up reading blueprints for work, then studied landscape architecture, and have worked my professional life thus far as a civil engineer – and loved working with maps. As I began my foray into creative writing, my first story idea involved a move into a mystical other realm within our known world. In order to facilitate my writing and at times clear my head I worked on drawing a map of the world within our world.

I have also started a model of this space that truly has helped me as I write. That said, in the process of researching and putting my thoughts and ideas into this paper I have learned much more that I know will help me as I continue, especially in character development.

To me the obvious and quickest connection between a map and story or writing is the setting. This also has been the easiest to write about. Moving the plot forward was also an easier concept – a map is used in a literal journey, why not a storyline? The use of a map in character development has been the greatest point of my discovery and the biggest “ah-ha” moment for me.

By creating and mapping out my main character’s past or back story I gained a deeper understanding of what makes him tick, how he will react, his mistrust of organized authority and the law system. By mapping out my protagonist’s past I found out what his deepest desire is, his greatest fear, and his default emotions and obsessions. These are what will make a character interesting, draw in readers, and cultivate that profluent plot.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, William. Goblin Secrets. Margaret K. McElderry Books, 2012.

Gardner, John. The Art of Fiction. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1983.

Kibuishi, Kazu. Amulet: Book One The Stone Keeper. Scholastic, 2008.

Martin, George R.R. A Song of Fire and Ice. Bantom Books, 1996.

Muehrcke, Phillip C. and Juliana O. Muehrcke. Geographical Review: Maps in Literature. American Geographical Society, Vol. 64, No. 3, pp. 317-338 July 1974.

Morrell, Jessica. Between the Lines: Master the Subtle Elements of Fiction Writing ebook. The Writer’s Digest, 2006.

Rothfuss, Patrick. The Wise Man’s Fear. DAW Books, Inc., 2011.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Hobbit. Houghton-Mifflin Company, 1966.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings Part I The Fellowship of the Ring. Houghton-Mifflin Company, 1965.

Turchi, Peter. Maps of the Imagination. Trinity University Press, 2004.

www.austinkleon.com/2008/05/21/maps-of-fictional-worlds/

www.living-death.tumblr.com

www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/league